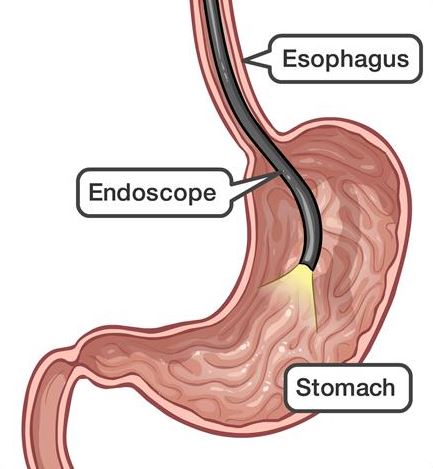

Endoscopy

Gastroscopy

This is usually a day procedure and is done under sedation. Patients should avoid driving for 24 hours upon discharge.

Colonoscopy

The usual indications for this procedure include passage of blood, positive faecal occult blood test, iron deficiency anaemia, altered bowel habits, family history of bowel cancer and surveillance for a history of colonic polyps or cancer. The common findings at colonoscopy especially in the middle-aged population are polyps and diverticulosis. Small polyps are removed and biopsies may be taken of any other pathology if necessary.

Adequate bowel cleansing is essential to enable a thorough visualisation of the bowel lining. Patients will be provided with an instruction sheet that outlines the dietary restrictions and oral preparation required.

This is usually a day procedure and patients should avoid driving for 24 hours in view of the sedation received.

Gallbladder Surgery

The common diseases associated with the gallbladder that will likely require surgery include

1. Symptomatic cholelithiasis (gallstones)

2. Cholecystitis ( an inflammed gallbladder usually due to stones)

3. Pancreatitis ( the pancreas becomes inflammed due to migration of a gallstone down the main/ common bile duct)

4. Cholangitis ( main bile duct infection usually due to the migrated stone that is wedged at the bottom of the duct and causing an obstruction)

5. Gallbladder polyps that are increasing in size

6. Large, asymptomatic stones and

7. Gallbladder cancer – fortunately this is rare

Surgery to remove the gallbladder is almost always performed in a keyhole fashion and is known as a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Often, a cholangiogram is performed concurrently where dye is used to outline the passages or biliary tree during surgery. Most patients are discharged after an overnight stay in hospital and return to work or undertake light duties after a fortnight.

Hernia

Common abdominal wall defects include inguinal, femoral, paraumbilical and incisional hernias

Colorectal Disease

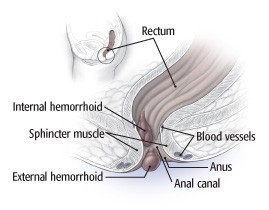

What are hemorrhoids?

The causes of haemorrhoids are not fully understood and likely multi-factorial. The blood vessels involved must continually battle gravity to get blood back up to the heart and some believe that symptomatic hemorrhoids are part of the price we pay for our upright posture!

These anal cushions have a non-vascular component consisting of epithelium, connective tissue and the muscle of Treitz. Treitz’s muscle tightly maintains the cushions in their normal position; its deterioration is considered one of the most important factors in the formation of hemorrhoids.

There are two kinds of hemorrhoids: internal hemorrhoids, which occur in the lower rectum, and external hemorrhoids, which develop under the skin around the anus. External hemorrhoids are the most uncomfortable, because the overlying skin becomes irritated and erodes. If a blood clot forms inside an external hemorrhoid, the pain can be sudden and severe. This is a thrombosed haemorrhoid and a painful lump is present around the anus. The clot usually dissolves, leaving excess skin (a skin tag), which may itch or become irritated.

Internal hemorrhoids are typically painless, even when they produce bleeding. You might, for example, see bright red blood on the toilet paper or dripping into the toilet bowl. Internal hemorrhoids may also prolapse, or extend beyond the anus, causing several potential problems. When a hemorrhoid protrudes, it can collect small amounts of mucus and tiny stool particles that may cause an irritation called pruritus ani. Wiping constantly to try to relieve the itching can worsen the problem.

There are various options to manage haemorrhoids

once the diagnosis has been confirmed. An important step is to avoid constipation. There are topical applications and suppositories that can be helpful to relieve pain and itching.

A banding procedure is often effective in managing internal haemorrhoids while surgery may be indicated if the above measures fail.

Our Practice Locations

Canberra

Calvary Bruce Private Hospital, 30 Mary Potter Circuit, Bruce ACT 2617

(02) – 6245 3128

(02) – 6245 3129

Bega

60 Upper St, Bega NSW 2550

(02) – 6492 0003

(02) – 8330 5525